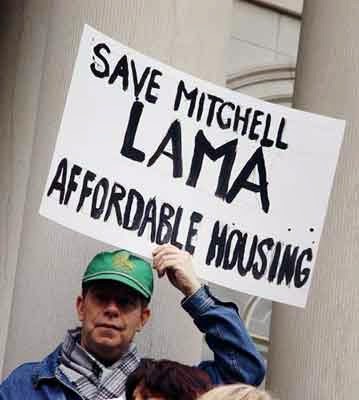

Thousands of Mitchell-Lama apartments in New York City -- created by a wonderfully successful NYS middle-income housing program-- are facing extinction.

Thousands of Mitchell-Lama apartments in New York City -- created by a wonderfully successful NYS middle-income housing program-- are facing extinction. Fortunately, there are resources to help. Check out Mitchell-Lama United renters and coop residents. That group includes the Mitchell-Lama Residents Coalition; and Cooperators United for Mitchell-Lama (CU4ML).

If the owners are threatening to take your building out of the Mitchell-Lama program, read (and download) the Buyout Handbook in English (2015). Then click on "read more" below for what happens in a "buyout."

This website primarily concerns rentals. If you want to keep your Mitchell-Lama co-op in the program, contact Cooperators United for Mitchell-Lama (CU4ML). and Mitchell-Lama United.

The year your building was built makes a difference. Tenants in developments built before 1974 are protected if taken out of Mitchell-Lama. They go into rent stabilization. But tenants in developments built later have little protection unless the state law changes.

FIND YOUR BUILDING , the year it was built, the "borough block and lot" numbers, and who represents you (updated Jan. 2018).

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

- What is "buying out" of the Mitchell-Lama program? (click on "read more" below for more detail)

BUYING OUT

of the MITCHELL-LAMA PROGRAM

What is “buying out” in a

Mitchell-Lama Rental building? (see

below for co-ops)

"Buying

out" means the landlord is pre-paying the mortgage for a building in order

to take it out of the Mitchell-Lama program.

It does not mean that the tenants get paid any money.

It's clearer to say "the owner is taking the building out of

the Mitchell-Lama program" -- but the expressions "buyout" or

"the landlord is buying out" are common on websites such as that of

the NYS Division of Housing and Community Renewal.

Aren't landlords entitled to buy

out of Mitchell-Lama after 20 years?

Yes but . .

. the question is what happens to the people who live in those buildings. Most

of us were never told that our apartment situations would change after 20 years

or so.

The

landlords have not suffered: Having invested in many cases only 5% of the

project's cost, they were given low-interest mortgage, tax breaks, and

guaranteed 6% profit (in most cases more) on their investment.

Affordable

housing is a necessity in New York City if the city is to function: we are the

people who staff the city's schools, libraries, hospitals, transit system,

social-work centers, theaters, and music and art programs. The City and State

made the decision that having middle income housing is crucial -- and that is

no less true now than it was in 1955 when Mitchell and Lama proposed their bill

to the New York State Legislature.

So to answer

a question with a question: Is the City's need for affordable housing outweighed

by a landlord's "need" to make more than 6% profit (and management

fees) on land that was virtually donated when the buildings were erected?

Can the tenants here buy our building to save it?

Yes, IF . .

.

NYC's

Housing Development Corporation (HDC) may let the tenants, the owner, a third

party, or some combination of those, convert their rental building to an

affordable co-op, if at least 25% (preferably more!) agree. Or a Community Land Trust or group such as the Urban Homesteading Assistance Board (UHAB) may help the

tenants buy it.

But there is

no requirement that the owner permit the tenants to buy it.

More

importantly, private equity firms are engaging in "predatory equity"

-- buying buildings as investments. They promise their investors far higher

returns than most landlords make -- returns only possible if all the

rent-regulated tenants are forced out. So some owners are not interested in

selling their building to the tenants even if the tenants offer them more money

than some predatory equity company -- particularly if the landlord has invested

in that company!

More

importantly, private equity firms are engaging in "predatory equity"

-- buying buildings as investments. They promise their investors far higher

returns than most landlords make -- returns only possible if all the

rent-regulated tenants are forced out. So some owners are not interested in

selling their building to the tenants even if the tenants offer them more money

than some predatory equity company -- particularly if the landlord has invested

in that company!

What happens to our rents if the

landlord takes us out of Mitchell-Lama?

If the

building was built before 1974, it goes into rent stabilization. Rents are regulated by the state under the

rules described on the NYC Rent Guidelines Board website.

If the

building was built after 1973, rents go to whatever the market will bear –

unless the tenant association negotiates a “Landlord Assistance Plan” to raise

the rents more slowly. Seniors and the

disabled in these buildings lose their “Senior Citizen Rent Increase Exemption”

or “Disability Rent Increase Exemption.”

In Mitchell-Lama Co-ops, “buying

out” means pre-paying the mortgage and leaving affordability and tax breaks.

What is a

Mitchell-Lama co-op? When the Mitchell-Lama program began in

1955, land was

given at low cost to developers to build either rental or co-op

buildings that would be and stay affordable to low- and middle-income

residents. The developers were also given low-interest government-subsidized

mortgages. To keep the developments affordable, the owners were given tax

abatements.

The apartments must be managed according to the state's Private

Housing Finance Law, and is supervised by an agency representing the level of

government that subsidized the mortgage: city (Department of Housing

Preservation and Development); state (NYS Homes and Community Renewal’s

Division of Housing & Community Renewal or DHCR); and federal (Department

of Housing and Urban Development).

Buyers,

chosen from the waiting list of those whose income makes them eligible, buy

shares in the co-op allowing them to live in their apartments. However, these

shareholders do not own their apartments outright.:

· they cannot

leave the apartment to someone when they die or let someone else live there

instead;

·

they cannot

sell it to anyone;

·

they cannot

mortgage their individual apartment.

Instead,

there is a waiting list, maintained by the supervising agency (HPD, DHCR, and

in some cases HUD), and expenditures must be in keeping with the affordability

requirements of state law.

Residents

who meet the financial qualifications buy their apartment for a fixed, low

cost, and later can sell it for roughly the same amount - so there is no profit

involved and the apartment remains affordable for the next buyer.

Why shouldn't residents take the co-op building out of Mitchell-Lama?

Here are

reasons* not to privatize a building:

1. The cost

goes up for those living there.

When a co-op

is taken out of Mitchell-Lama, it loses its tax abatements and must pre-pay its

government-subsidized mortgage. That generally means taking out another

mortgage, often at higher cost.

With new tax

bills to pay and possibly higher mortgage costs, the costs of running the

building increase - and that means higher monthly maintenance costs for

residents.

In addition,

those residents who hope to sell their apartments for lots of money may want

the building to look nicer, and may push for cosmetic and other

"improvements" whose costs will be shared among all the building's

residents.

2. The

Purpose Changes.

The purpose

of Mitchell-Lamas, set out in Article II of the Private Housing Finance Law, is

to provide affordable homeownership to "persons or families of low

income."

Mitchell-Lamas

- both rentals and co-ops - are technically non-profit corporations set up to

make that purpose a reality.

In co-ops, middle-income people buy shares

(so they become "shareholders") that allow them to live in a

particular apartment. When they leave the apartment (or die), the

"shareholder" is entitled to whatever they paid, plus the small

increase in the value of the building resulting from paying off part or all of

the mortgage. (Shareholders cannot sell their apartments to anyone, leave them

to someone in their will, mortgage them, or otherwise earn a profit from them.)

The next shareholder will be taken from the waiting list, supervised by the

government agency of the level holding the mortgage.

·

City

mortgage-held buildings are supervised by the city's Department of Housing

Preservation & Development.

·

State

mortgage-held buildings are supervised by the state's Division of Housing &

Community Development.

·

Federal

mortgage-held buildings are supervised by HUD.

If the

shareholders vote to "privatize" their building (take it out of

Mitchell-Lama), the building

- loses its tax abatement, and

- must pay off its government-subsidized mortgage and get another mortgage on the free market.

More importantly for this discussion, privatization means changing

the kind of corporation that is the legal form for the building. As the

Cooperators United for Mitchell-Lama note, it is no longer a non-profit entity

set up to "serve a public purpose." Instead it becomes a for-profit

entity authorized to promote the private monetary interests of its

shareholders, without any regard for those the Mitchell-Lama program intended

to benefit.

3. The

Control Changes.

While the

co-op building is in Mitchell-Lama, it is supervised by a government agency.

The co-op board is legally required to operate the project "in the most

economical manner" for the financial and physical integrity of the

building, and the supervisory agency (HPD or DHCR) oversees this duty.

But if a

co-op leaves Mitchell-Lama, and becomes a "for profit" organization,

HPD and DHCR no longer oversee the buildings, there are no more waiting lists

of income-eligible applicants, and the new for-profit corporation gets complete

control over these issues.

___________________

*Thanks to Joan Meyler of CU4ML (Cooperators United for Mitchell-Lama) for articulating points 1,

2 and 3 in a letter to then-NYC Comptroller Thompson and Dept. of Finance

Commissioner Stark .

____________________

4. The

People Who Benefit Change.

While the

co-op is still in Mitchell-Lama, the supervising agencies make sure that

affordable homes are available to the current shareholders (owners) and to the

low- and middle-income people who qualify to be on the waiting list.

But as soon

as the co-op changes from Mitchell-Lama to a for-profit organization, there is

no more waiting list, and no more concern for those who will need affordable

housing in the future. Instead, the people who formerly had only the right to

live there as long as they lived (but couldn't pass it on to others), would now

own it outright, and could do what they wanted with it. All the public

subsidies would go to enrich them privately. And public policy on issues like

affordable housing for future generations would have no more effect.

5. Buildings

can get the financial support they need (up to $15 million) interest free to

make necessary repairs, so there is no need to privatize.

The state's

Housing Finance Administration and the City's Housing Development Corporation

are offering loans (the HFA loans are interest-free for up to $15 million to

state-supervised Mitchell-Lamas) to help buildings make necessary repairs and

stay in Mitchell-Lama. See HFA's program, the Mitchell Lama

Rehabilitation and Preservation" project.

No comments:

Post a Comment